A whiff of heritage

An afternoon at Mirza Ghalib’s favourite perfumery takes you back aeons, says KRISHNARAJ IYENGAR

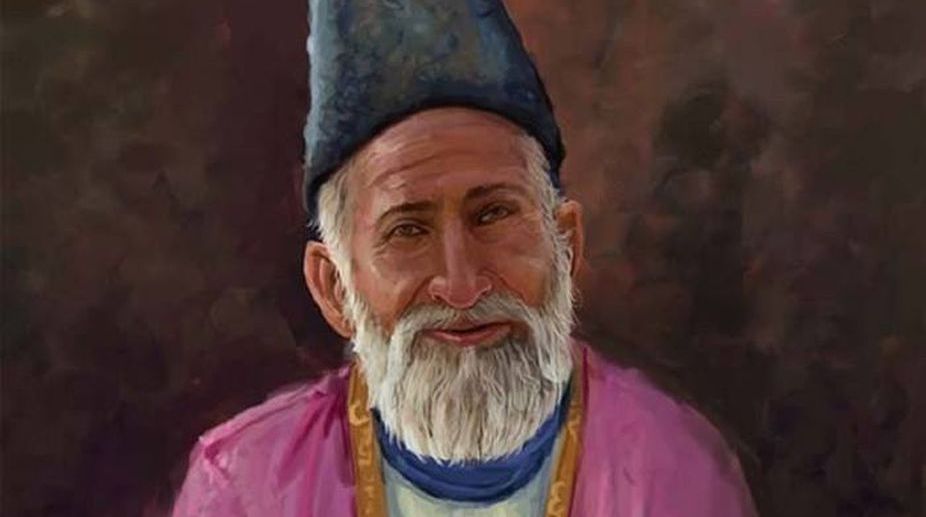

Mirza Ghalib (Photo: Facebook/ Representational Iimage)

After Ghalib’s death, among those who courted the Urdu Muse in the 20th Century the name of Jigar Moradabadi enjoys an exalted place.

Though deprived of the benefits of a formal education enjoyed the shairs like Fani, Iqbal and Faiz, he was able to weave a magic in his verse that still remains unsurpassed. Harivansh Rai Bacchan was a latter-day entrant to the Madhushala, but Jigar had seduced both the Saqi and the Jaam much earlier, before stumbling out of the Maikhana, or the intoxicating Eastern tavern, which had eluded the older Urdu poets like Hir, Sauda and Mazhar Jan-e-Jana. It was on September 9,1960 that this great lyricist of Urdu poetry died after a long and eventful life.

Advertisement

Born in 1980, nearly 21 years after the death of Ghalib, Jigar came into prominence in 1928. The year saw death of Thomas Hardy the great English novelist and also that of Lazarus, a scion of the famous family of the military adventurer Colonel Salvador Smith of the Gwalior State Army.

Advertisement

Hardy died full of years, Lazarus in the prime of life, not fully aware of the greartness that Jigar was to reap in later years. A contemporary of such stalwarts as Josh, Fani and Asghar, the latter also his friend, and guide, Jigar moulded the ghazal to his heart’s desire and left it adorned like the proverbial wine-cup of Omar Khayyam.

There were times when he was so drunk that he could utter only monosyllables in the bethak(sitting room), his hair dishevelled like a madman’s, his clothes all crumpled up by having being worn too long, his beard growing wild and his eyes even wilder. But then the muse suddenly asserted herself and Jigar came back to his senses with a bang and a ghazal so spontaneous that it defied the diction laid down by Wordsworth, “Powerful emotion recollected in tranquility. For Jigar the experience was anything but tranquil.

Perhaps few shairsin Urdu poetry may be able to touch the emotional depths of Jigar (literally, the liver, and figuratively the spleen). His last collected work, Atish-e-Gul published just a year before his death, personifies his character to a great extent for he was allatish(fire, surely the fire of emotion that smoulders deep under but never dies) so that feelings could bloom like a rose. Barging into the tavern soon afterJigar was Firaq.

Anything connected with Raghupati Sahai, Firaq Gorakhpuri , excites interest and curiosity, especially incidents relating to his life. And who can relate them better than Ramesh Chandra Diwedi, Firaq’s companion for many years right up to the poet’s death in 1982 . Diwedi’s tribute to his ustad is a veritable treasure for all those who have been fascinated by this eccentric man who strode the literary world of his time like a colossus with only Josh and later Faiz to rival him. He liked Ghalib, Gandhi, Nehru and Wordsworth, but not Iqbal, and craved for the comapny of Majaz.

But he had his shortcomings all right. A morbid fear of American capitalism made him scan the morning papers for an assurance that was well with the world, his leftist leanings saw a savior in Russia but Pakistan continued to remain a bug-bear.

This is the 36th year of the death of Josh Malihabadi, but memories of this doyen of Urdu poetry seem to be fading from the public mind. Yet there was a time when Josh's qalaminfused enthusiasm in the hearts of not only freedom fighters but also those espousing the cherished ideals of equality, religious liberty and fraternity.

Shabbir Hussein Khan, who took the pseudonym of Josh, was a year younger than Firaq Gorakhpuri, though the latter considered him his senior and, on his own admission once went to him hesitantly to seek the correct word which had been eluding him in a ghazal. Josh barked out the word as though spitting out a gem ~ or so Firaq implied in a TV interview in 1981 on hearing of the death of his contemporary in Lahore.

Josh was an aristocrat from a zamindar family of U.P., who became a socialist early in life despite his upbringing as a Pathan landlord. One was his neighbour for three months in 1967, when he came from Pakistan and occupied the room next to this scribe's in Azad Hind Hotel.

He lived in Room No. 4 and his wife in the adjacent room. The begum kept a stern eye on the poet, peeping from behind the curtain to see whom he was talking to. His younger brother, who looked after the family's dussehri mango orchards in Malihabad, near Lucknow, shared the room with him and prepared the hookah for both of them to smoke with long pauses of silence as they chewed the cud of nostalgia. Hussaini Chacha, as he was called by the hotel staff, was just as deeply ingrained in literary culture and etiquette as his brother.

Many poets used to come to meet Josh, among them Gulzar Dehlvi, Bekhud, Betaab and of course the hotel owner, who wrote erotic poetry. Josh a fair, balding bigbuilt man with moustaches and dressed in KurtaPyjama, had become a bit senile, which some attributed to the death of his daughter at Thompson Hospital, Agra. Anglo-Indian Sister Queeny, who conveyed the sad news to him in Dec 1935 in English, found Josh not so ignorant of the language, though he was helped by two young men. Josh let vent to his grief in poetry but his wife just couldn't get over it and became a recluse. At the hotel in Jama Masjid Josh held court every evening when people from walks all of life came to meet him, among them Saeed Naqvi and his maternal uncle, Mehdi.

Some read out their poems. Sahba once came with a soapdish in hand, his face unwiped, asking for Betaab Sahib. Josh replied “Betaab Sahib yahan kahan, kahin betaab ghoom rahe honge. Lekin aap apna moonh tau ponhch lijye.” Betaab means restless and the poet's reply that he must be wandering restless somewhere amused everyone present. Josh used to have an early dinner of chicken, naan, biryani and kababs, washed down with two pegs of Scotch whisky, sent every evening by the proprietor of Moti Mahal restaurant in Daryaganj.

After that he would go to sleep and get up before 4 o'clock when after his ablutions, he sat down to write poetry till 6.30 a.m. Then he ate breakfast, which included nahari from Karim's. After that he had a bath and went out to meet his friends in New Delhi, mostly high officials.

Twice or thrice he went to see Indira Gandhi and each time returned praising her. Lunch he mostly had outside and on his return only the gurgling hookah and occasional conversation with Hussaini Chacha marked the afternoon's transformation into evening.

When he left for Lahore one was aware that one had seen a literary colossus at close quarters and that one day his reminiscences should make good copy for newspaper readers.

Advertisement